Template Syntax 6.0

Last updated: 2019-01-08

This page covers the basic elements of the Angular template syntax for constructing views.

The Angular app manages what the user sees and can do, achieving this through the interaction of a component class instance (the component) and its user-facing template.

You might be familiar with the combination of component and template from experience with model-view-controller (MVC) or model-view-viewmodel (MVVM). In Angular, the component plays the part of the controller/viewmodel, and the template represents the view.

The live example (view source) demonstrates all of the syntax and code snippets described in this page.

HTML in templates

HTML is the language of the Angular template.

Almost all HTML syntax is valid template syntax.

The <script> element is a notable exception;

it’s forbidden, eliminating the risk of script injection attacks.

In practice, <script> is ignored and a warning appears in the browser console.

See the Security page for details.

Some legal HTML doesn’t make much sense in a template.

The <html>, <body>, and <base> elements have no useful role.

Pretty much everything else can be used.

You can extend the HTML vocabulary of templates with components and directives that appear as new elements and attributes. In the following sections, you’ll learn how to get and set DOM (Document Object Model) values dynamically through data binding.

Begin with the first form of data binding—interpolation—to see how much richer template HTML can be.

Interpolation ( {{…}} )

You met the double-curly braces of interpolation, {{ and }}, early in your Angular education.

<p>My current hero is {{currentHero.name}}</p>You use interpolation to weave calculated strings into the text between HTML element tags and within attribute assignments.

<h3>

{{title}}

<img src="{{heroImageUrl}}" style="height:30px">

</h3>The text between the braces is often the name of a component property. Angular replaces that name with the

string value of the corresponding component property. In the example above, Angular evaluates the title and heroImageUrl properties

and “fills in the blanks”, first displaying a bold app title and then a heroic image.

More generally, the text between the braces is a template expression that Angular first evaluates and then converts to a string. The following interpolation illustrates the point by adding the two numbers:

<!-- "The sum of 1 + 1 is 2" -->

<p>The sum of 1 + 1 is {{1 + 1}}</p>The expression can invoke methods of the host component such as getVal(), seen here:

<!-- "The sum of 1 + 1 is not 4" -->

<p>The sum of 1 + 1 is not {{1 + 1 + getVal()}}</p>Angular evaluates all expressions in double curly braces, converts the expression results to strings, and links them with neighboring literal strings. Finally, it assigns this composite interpolated result to an element or directive property.

From a quick glance at the syntax, it looks as if you’re inserting the result between element tags and assigning it to attributes. That’s a convenient way to think of what’s happening, but it’s not exactly true. Interpolation is a special syntax that Angular converts into a property binding. See the details below.

But first, let’s take a closer look at template expressions and statements.

Template expressions

A template expression produces a value. Angular executes the expression and assigns it to a property of a binding target; the target might be an HTML element, a component, or a directive.

The interpolation braces in {{1 + 1}} surround the template expression 1 + 1.

In the property binding section below,

a template expression appears in quotes to the right of the = symbol, as in [property]="expression".

You write these template expressions in a language that looks like Dart. Many Dart expressions are legal template expressions, but not all are.

Dart expressions that have or promote side effects are prohibited, including the following:

- Assignments (

=,+=,-=, …) -

neworconst - Chaining expressions with

; - Increment and decrement operators (

++and--)

Other notable differences from Dart syntax include the following:

- No support for Dart string interpolation; for example,

instead of

"'The title is $title'", you must write"'The title is ' + title" - No support for the bitwise operators

|and& - New template expression operators, such as

|

Expression context

The expression context is typically the component instance.

In the following snippets, the title within double curly braces and the

isUnchanged in quotes refer to properties of the AppComponent.

{{title}}

<span [hidden]="isUnchanged">changed</span>An expression can also refer to properties of the template’s context,

such as a template input variable (let hero)

or a template reference variable (#heroInput).

<div *ngFor="let hero of heroes">{{hero.name}}</div>

<input #heroInput> {{heroInput.value}}The context for terms in an expression is a blend of the template variables and the component’s members. If you reference a name that belongs to more than one of these namespaces, the template variable name takes precedence, followed by a name in the directive’s context, and, lastly, the component’s member names.

The previous example presents such a name collision. The component has a hero

property and the *ngFor defines a hero template variable.

The hero in {{hero.name}}

refers to the template input variable, not the component’s property.

Template expressions can refer to top-level and static-member constants and

functions that are listed in a component’s exports argument.

import 'dart:math' as math;

// ···

enum Color { red, green, blue }

// ···

@Component(

// ···

exports: [Color, math.min],

// ···

)

class AppComponent implements OnInit {

// ···

}Access members of exported enums using the usual syntax:

The name of the Color.red enum is {{Color.red}}.<br>Expression guidelines

Template expressions can make or break an app. Follow these guidelines:

If you make an exception to the above guidelines, make sure you thoroughly understand the circumstances.

No visible side effects

A template expression must not change any app state other than the value of the target property.

This rule is essential to Angular’s “unidirectional data flow” policy. It ensures that reading a component value doesn’t change some other displayed value. The view must be stable throughout a single rendering pass.

Quick execution

Angular executes template expressions after every change detection cycle. Change detection cycles are triggered by many asynchronous activities such as promise resolutions, http results, timer events, keypresses and mouse moves.

Expressions need to finish quickly or the user experience might drag, especially on slower devices. Consider caching values when their computation is expensive.

Simplicity

Although it’s possible to write quite complex template expressions, it’s best to avoid them.

In most situations, use a property name or method call.

An occasional Boolean negation (!) is OK.

Otherwise, confine application and business logic to the component itself,

where it’s easier to develop and test.

Idempotence

An idempotent expression is ideal because it’s free of side effects and improves Angular’s change detection performance.

In Angular terms, an idempotent expression always returns exactly the same thing until one of its dependent values changes.

Dependent values should not change during a single turn of the event loop.

If an idempotent expression returns a string or a number, it returns the same string or number

when called twice in a row. If the expression returns an object (including a List),

it returns the same object reference when called twice in a row.

Template statements

A template statement responds to an event raised by a binding target

such as an element, component, or directive.

You’ll see template statements in the event binding section

appearing in quotes to the right of the = symbol as in (event)="statement".

<button (click)="deleteHero()">Delete hero</button>A template statement has a side effect. That’s the whole point of an event. It’s how you update app state from user action.

Responding to events is the other side of Angular’s “unidirectional data flow”. You’re free to change anything, anywhere, during this turn of the event loop.

Like template expressions, template statements use a language that looks like Dart.

The template statement parser differs from the template expression parser and

specifically supports both basic assignment (=) and chaining expressions

(with ;).

However, the following Dart syntax is not allowed:

-

neworconst - Increment and decrement operators,

++and-- - Operator assignment, such as

+=and-= - The bitwise operators

|and& - The template expression operators

Statement context

As with expressions, statements can refer only to what’s in the statement context such as an event handling method of the component instance.

The statement context is typically the component instance.

The deleteHero in (click)="deleteHero()" is a method of the data-bound component.

<button (click)="deleteHero()">Delete hero</button>The statement context can also refer to properties of the template’s own context.

In the following examples, the template $event object,

a template input variable (let hero),

and a template reference variable (#heroForm)

are passed to an event handling method of the component.

<button (click)="onSave($event)">Save</button>

<button *ngFor="let hero of heroes" (click)="deleteHero(hero)">{{hero.name}}</button>

<form #heroForm (ngSubmit)="onSubmit(heroForm)"> ... </form>Template context names take precedence over component context names.

In deleteHero(hero) above, the hero is the template input variable,

not the component’s hero property.

Template statements can refer to top-level and static-member constants and

functions that are listed in a component’s exports argument.

For details, see the discussion of exports in the section on

Expression context.

Statement guidelines

As with expressions, avoid writing complex template statements. Method calls or simple property assignments are best.

Now that you have a feel for template expressions and statements, you’re ready to learn about the varieties of data binding syntax beyond interpolation.

Binding syntax: An overview

Data binding is a mechanism for coordinating what users see, with app data values. While you can push values to and pull values from HTML, the app is easier to write, read, and maintain if you use a binding framework. You declare bindings between binding sources and target HTML elements and then let the framework do the work.

Below is a high-level summary of Angular data binding and its syntax. It’s followed by more detailed information about most of the data binding types that Angular provides.

Binding types can be grouped into three categories based on the direction of data flow: source-to-view, view-to-source, and two-way sequence view-to-source-to-view.

| Data direction | Syntax | Type |

|---|---|---|

| One-way from data source to view target |

|

Interpolation Property Attribute Class Style |

| One-way from view target to data source |

|

Event |

| Two-way |

|

Two-way |

Binding types other than interpolation have a target name to the left of the equal sign,

either surrounded by punctuation ([], (), [()]) or preceded by a prefix (bind-, on-).

The target name is the name of a property. It might look like the name of an attribute but it never is. To appreciate the difference, you must develop a new way to think about template HTML.

A new mental model

With all the power of data binding and the ability to extend the HTML vocabulary with custom markup, it’s tempting to think of template HTML as HTML Plus.

It really is HTML Plus. But it’s also significantly different from the HTML you’re used to. It requires a new mental model.

In the normal course of HTML development, you create a visual structure with HTML elements, and you modify those elements by setting element attributes with string constants.

<div class="special">Mental Model</div>

<img src="assets/images/hero.png">

<button disabled>Save</button>You still create a structure and initialize attribute values this way in Angular templates.

Then you learn to create new elements with components that encapsulate HTML and drop them into templates as if they were native HTML elements.

<!-- Normal HTML -->

<div class="special">Mental Model</div>

<!-- Wow! A new element! -->

<my-hero></my-hero>That’s HTML Plus.

Then you learn about data binding. The first binding you meet might look like this:

<!-- Bind button disabled state to `isUnchanged` property -->

<button [disabled]="isUnchanged">Save</button>Your intuition might suggest that you’re binding to the button’s disabled attribute and setting

it to the current value of the component’s isUnchanged property. That intuition would be incorrect!

The everyday HTML mental model is misleading. Once you start data binding, you’re no longer working with HTML attributes. You aren’t setting attributes; you’re setting the properties of DOM elements, components, and directives.

HTML attribute vs. DOM property

The distinction between an HTML attribute and a DOM property is crucial to understanding how Angular binding works.

Attributes are defined by HTML. Properties are defined by the DOM (Document Object Model).

-

A few HTML attributes have 1:1 mapping to properties.

idis one example. -

Some HTML attributes don’t have corresponding properties.

colspanis one example. -

Some DOM properties don’t have corresponding attributes.

textContentis one example. -

Many HTML attributes appear to map to properties … but not in the way you might think!

That last category is confusing unless you know this general rule:

Attributes initialize DOM properties and then they’re done. Property values can change; attribute values can’t.

For example, when the browser renders <input type="text" value="Bob">, it creates a

corresponding DOM node with a value property initialized to “Bob”.

When the user enters “Sally” in the input box, the DOM element value property becomes “Sally”.

But the HTML value attribute remains unchanged, as you discover if you ask the input element

about that attribute: input.getAttribute('value') returns “Bob”.

The HTML attribute value specifies the initial value; the DOM value property is the current value.

The disabled attribute is another peculiar example. A button’s disabled property is

false by default so the button is enabled.

When you add the disabled attribute, its presence alone initializes the button’s disabled property to true

so the button is disabled.

Adding and removing the disabled attribute disables and enables the button. The value of the attribute is irrelevant,

which is why you can’t enable a button by writing <button disabled="false">Still Disabled</button>.

Setting the button’s disabled property (say, with an Angular binding) disables or enables the button.

The value of the property matters.

The HTML attribute and the DOM property are not the same thing, even when they have the same name.

This fact bears repeating: Template binding works with properties and events, not attributes.

A world without attributes

In the world of Angular, the only role of attributes is to initialize element and directive state. When you write a data binding, you’re dealing exclusively with properties and events of the target object. HTML attributes effectively disappear.

With this model in mind, read on to learn about binding targets.

Binding targets

The target of a data binding is something in the DOM. Depending on the binding type, the target can be an (element | component | directive) property, an (element | component | directive) event, or (rarely) an attribute name. The following table summarizes the scenarios:

| Type | Target | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Property | Element property Component property Directive property |

|

| Event | Element event Component event Directive event |

|

| Two-way | Event and property |

|

| Attribute | Attribute (the exception) |

|

| Class |

class property |

|

| Style |

style property |

|

You’re now ready to look at binding types in detail.

Property binding ( [property] )

Write a template property binding to set a property of a view element. The binding sets the property to the value of a template expression.

The most common property binding sets an element property to a component property value. An example is

binding the src property of an image element to a component’s heroImageUrl property:

<img [src]="heroImageUrl">Another example is disabling a button when the component says that it isUnchanged:

<button [disabled]="isUnchanged">Cancel is disabled</button>Another is setting a property of a directive:

<div [ngClass]="classes">[ngClass] binding to the classes property</div>Yet another is setting the model property of a custom component (a great way for parent and child components to communicate):

<my-hero [hero]="currentHero"></my-hero>One-way in

People often describe property binding as one-way data binding because it flows a value in one direction, from a component’s data property into a target element property.

You can’t use property binding to pull values out of the target element. You can’t bind to a property of the target element to read it.; you can only set it.

Similarly, you can’t use property binding to call a method on the target element.

If the element raises events, you can listen to them with an event binding.

If you must read a target element property or call one of its methods, you need a different technique. See the API reference for ViewChild and ContentChild.

Binding target

An element property between enclosing square brackets identifies the target property.

The target property in the following code is the image element’s src property.

<img [src]="heroImageUrl">Some people prefer the bind- prefix alternative, known as the canonical form:

<img bind-src="heroImageUrl">The target name is always the name of a property, even when it appears to be the name of something else.

You might see src and think it’s the name of an attribute. It’s not; it’s the name of an image element property.

Element properties might be the more common targets, but Angular looks first to see if the name is a property of a known directive, as it is in the following example:

<div [ngClass]="classes">[ngClass] binding to the classes property</div>Technically, Angular is matching the name to a directive input

or a property decorated with @Input(). Such inputs map to the directive’s own properties.

If the name fails to match a property of a known directive or element, Angular reports an “unknown directive” error.

Avoid side effects

As mentioned previously, the evaluation of a template expression must have no visible side effects. The expression language itself does its part to keep you safe. You can’t assign a value to anything in a property binding expression nor use the increment and decrement operators.

Of course, the expression might invoke a property or method that has side effects. Angular has no way of knowing that or stopping you.

The expression could call something like getFoo(). Only you know what getFoo() does.

If getFoo() changes something and you happen to be binding to that something, you risk an unpleasant experience.

Angular may or may not display the changed value. Angular may detect the change and throw a warning error.

In general, stick to data properties and to methods that return values and do no more.

Return the proper type

The template expression should evaluate to the type of value expected by the target property.

The hero property of HeroComponent expects a Hero object, which is exactly what you’re sending in the property binding:

<my-hero [hero]="currentHero"></my-hero>Remember the brackets

The brackets tell Angular to evaluate the template expression. If you omit the brackets, Angular treats the string as a constant and initializes the target property with that string. It does not evaluate the string!

If you forget the brackets around the hero property like this:

<-- DON'T do this: -->

<my-hero hero="currentHero"></my-hero>You’ll get the following build error:

[error] A value of type 'String' can't be assigned to a variable of type 'Hero'.

One-time string initialization

Omit the brackets when all of the following are true:

- The target property accepts a string value.

- The string is a fixed value that you can bake into the template.

- This initial value never changes.

One-time string initialization is routine in standard HTML, and

it works just as well for directive and component properties.

The following example initializes the prefix property of the HeroComponent to a fixed string,

not a template expression. Angular sets it and forgets about it.

<my-hero prefix="You are my" [hero]="currentHero"></my-hero>The [hero] binding, on the other hand, remains a live binding to the component’s currentHero property.

Property binding or interpolation?

You often have a choice between interpolation and property binding. The following binding pairs do the same thing:

<p><img src="{{heroImageUrl}}"> is the <i>interpolated</i> image.</p>

<p><img [src]="heroImageUrl"> is the <i>property bound</i> image.</p>

<p><span>"{{title}}" is the <i>interpolated</i> title.</span></p>

<p>"<span [innerHTML]="title"></span>" is the <i>property bound</i> title.</p>Interpolation is a convenient alternative to property binding in many cases.

When rendering data values as strings, there is no technical reason to prefer one form to the other, but interpolation can be more readable. We suggest establishing coding style rules and choosing the form that both conforms to the rules and feels most natural for the task at hand.

When setting an element property to a non-string data value, you must use property binding.

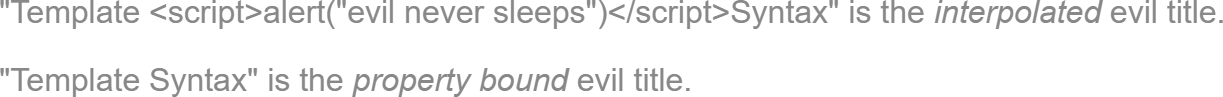

Content security

Imagine the following malicious content.

String evilTitle =

'Template <script>alert("evil never sleeps")</script>Syntax';Fortunately, Angular data binding is on alert for dangerous HTML. It sanitizes the values before displaying them. It does not allow HTML with script tags to leak into the browser, neither with interpolation nor property binding.

<!--

Angular generates warnings for these two lines as it sanitizes them

WARNING: sanitizing HTML stripped some content (see http://g.co/ng/security#xss).

-->

<p><span>"{{evilTitle}}" is the <i>interpolated</i> evil title.</span></p>

<p>"<span [innerHTML]="evilTitle"></span>" is the <i>property bound</i> evil title.</p>Interpolation handles the script tags differently than property binding but both approaches render the content harmlessly.

Attribute, class, and style bindings

The template syntax provides specialized one-way bindings for scenarios less well suited to property binding.

Attribute binding

You can set the value of an attribute directly with an attribute binding.

This is the only exception to the rule that a binding sets a target property. This is the only binding that creates and sets an attribute.

This guide stresses repeatedly that setting an element property with a property binding is always preferred to setting the attribute with a string. Why does Angular offer attribute binding?

You must use attribute binding when there is no element property to bind.

Consider the ARIA, SVG, and table span attributes. They are pure attributes. They do not correspond to element properties, and they do not set element properties. There are no property targets to bind to.

This fact becomes painfully obvious when writing something like this:

<tr><td colspan="{{1 + 1}}">Three-Four</td></tr>

The result is this error:

Template parse errors:

Can't bind to 'colspan' since it isn't a known native property

As the message says, the <td> element does not have a colspan property.

It has the “colspan” attribute, but

interpolation and property binding can set only properties, not attributes.

You need attribute bindings to create and bind to such attributes.

Attribute binding syntax resembles property binding.

Instead of an element property between brackets, start with the prefix attr,

followed by a dot (.) and the name of the attribute.

You then set the attribute value, using an expression that resolves to a string.

Bind [attr.colspan] to a calculated value:

<table border="1">

<!-- expression calculates colspan=2 -->

<tr><td [attr.colspan]="1 + 1">One-Two</td></tr>

<!-- ERROR: There is no `colspan` property to set!

<tr><td colspan="{{1 + 1}}">Three-Four</td></tr>

-->

<tr><td>Five</td><td>Six</td></tr>

</table>Here’s how the table renders:

| One-Two | |

| Five | Six |

One of the primary use cases for attribute binding is to set ARIA attributes, as in this example:

<!-- create and set an aria attribute for assistive technology -->

<button [attr.aria-label]="actionName">{{actionName}} with Aria</button>Class binding

You can add and remove CSS class names from an element’s class attribute with

a class binding.

Class binding syntax resembles property binding.

Instead of an element property between brackets, start with the prefix class,

optionally followed by a dot (.) and the name of a CSS class: [class.class-name].

The following examples show how to add and remove the app’s “special” class with class bindings. Here’s how to set the attribute without binding:

<!-- standard class attribute setting -->

<div class="bad curly special">Bad curly special</div>You can replace that with a binding to a string of the desired class names; this is an all-or-nothing, replacement binding.

<!-- reset/override all class names with a binding -->

<div class="bad curly special"

[class]="badCurly">Bad curly</div>Finally, you can bind to a specific class name. Angular adds the class when the template expression evaluates to true. It removes the class when the expression is false.

<!-- toggle the "special" class on/off with a property -->

<div [class.special]="isSpecial">The class binding is special</div>

<!-- binding to `class.special` trumps the class attribute -->

<div class="special"

[class.special]="!isSpecial">This one is not so special</div>While this is a fine way to toggle a single class name, the NgClass directive is usually preferred when managing multiple class names at the same time.

Style binding

You can set inline styles with a style binding.

Style binding syntax resembles property binding.

Instead of an element property between brackets, start with the prefix style,

followed by a dot (.) and the name of a CSS style property: [style.style-property].

<button [style.color]="isSpecial ? 'red': 'green'">Red</button>

<button [style.background-color]="canSave ? 'cyan': 'grey'" >Save</button>Some style binding styles have a unit extension. The following example conditionally sets the font size in “em” and “%” units .

<button [style.font-size.em]="isSpecial ? 3 : 1" >Big</button>

<button [style.font-size.%]="!isSpecial ? 150 : 50" >Small</button>While this is a fine way to set a single style, the NgStyle directive is generally preferred when setting several inline styles at the same time.

Note that a style property name can be written in either

dash-case, as shown above, or

camelCase, such as fontSize.

Style property names

While camelCase and

dash-case style property naming schemes are

equivalent in AngularDart, only dash-case names are recognized by the

dart:html CssStyleDeclaration methods getPropertyValue()

and setProperty().

So using dash-case for style property names is generally preferred.

Event binding ( (event) )

The bindings directives you’ve met so far flow data in one direction: from a component to an element.

Users don’t just stare at the screen. They enter text into input boxes. They pick items from lists. They click buttons. Such user actions can result in a flow of data in the opposite direction: from an element to a component.

The only way to know about a user action is to listen for certain events such as keystrokes, mouse movements, clicks, and touches. You declare your interest in user actions through Angular event binding.

Event binding syntax consists of a target event name

within parentheses on the left of an equal sign, and a quoted

template statement on the right.

The following event binding listens for the button’s click events, calling

the component’s onSave() method whenever a click occurs:

<button (click)="onSave()">Save</button>Target event

A name between parentheses — for example, (click) —

identifies the target event. In the following example, the target is the button’s click event.

<button (click)="onSave()">Save</button>Some people prefer the on- prefix alternative, known as the canonical form:

<button on-click="onSave()">On Save</button>Element events might be the more common targets, but Angular looks first to see if the name matches an event property of a known directive, as it does in the following example:

<!-- `myClick` is an event on the custom `ClickDirective` -->

<div (myClick)="clickMessage=$event" clickable>click with myClick</div>The myClick directive is further described in the section

on aliasing input/output properties.

If the name fails to match an element event or an output property of a known directive, Angular reports an “unknown directive” error.

$event and event handling statements

In an event binding, Angular sets up an event handler for the target event.

When the event is raised, the handler executes the template statement. The template statement typically involves a receiver, which performs an action in response to the event, such as storing a value from the HTML control into a model.

The binding conveys information about the event, including data values, through

an event object named $event.

The shape of the event object is determined by the target event.

If the target event is a native DOM element event, then $event is a

DOM event object,

with properties such as target and target.value.

Consider this example:

<input [value]="currentHero.name"

(input)="currentHero.name=$event.target.value" >This code sets the input box value property by binding to the name property.

To listen for changes to the value, the code binds to the input box’s input event.

When the user makes changes, the input event is raised, and the binding executes

the statement within a context that includes the DOM event object, $event.

To update the name property, the changed text is retrieved by following the path $event.target.value.

If the event belongs to a directive (recall that components are directives),

$event has whatever shape the directive decides to produce.

Custom events

Directives typically raise custom events using a StreamController.

The directive creates a StreamController and exposes its underlying stream as a property.

The directive calls StreamController.add(payload) to fire an event, passing in a message payload, which can be anything.

Parent directives listen for the event by binding to this property and accessing the payload through the $event object.

Consider a HeroComponent that presents hero information and responds to user actions.

Although the HeroComponent has a delete button it doesn’t know how to delete the hero itself.

The best it can do is raise an event reporting the user’s delete request.

Here are the pertinent excerpts from that HeroComponent:

lib/src/hero_component.dart (template)

template: '''

<div>

<img src="{{heroImageUrl}}">

<span [style.text-decoration]="lineThrough">

{{prefix}} {{hero?.name}}

</span>

<button (click)="delete()">Delete</button>

</div>

''',lib/src/hero_component.dart (deleteRequest)

final _deleteRequest = StreamController<Hero>();

@Output()

Stream<Hero> get deleteRequest => _deleteRequest.stream;

void delete() {

_deleteRequest.add(hero);

}The component defines a private StreamController property and

exposes the controller’s stream through the deleteRequest getter.

When a user clicks Delete, the component’s delete() method is called,

directing the StreamController to add a Hero to the stream.

Now imagine a hosting parent component that binds to the HeroComponent’s deleteRequest event.

<my-hero (deleteRequest)="deleteHero($event)" [hero]="currentHero"></my-hero>When the deleteRequest event fires, Angular calls the parent component’s deleteHero method,

passing the hero-to-delete (emitted by HeroDetail) in the $event variable.

Template statements have side effects

The deleteHero method has a side effect: it deletes a hero.

Template statement side effects are not just OK, but expected.

Deleting the hero updates the model, perhaps triggering other changes including queries and saves to a remote server. These changes percolate through the system and are ultimately displayed in this and other views.

Two-way binding ( [(…)] )

You often want to both display a data property and update that property when the user makes changes.

On the element side that takes a combination of setting a specific element property and listening for an element change event.

Angular offers a special two-way data binding syntax for this purpose, [(x)].

The [(x)] syntax combines the brackets

of property binding, [x], with the parentheses of event binding, (x).

[( )] = banana in a box

Visualize a banana in a box to remember that the parentheses go inside the brackets.

The [(x)] syntax is easy to demonstrate when the element has a settable property called x

and a corresponding event named xChange.

Here’s a SizerComponent that fits the pattern.

It has a size value property and a companion sizeChange event:

lib/src/sizer_component.dart

import 'dart:async';

import 'dart:math';

import 'package:angular/angular.dart';

const minSize = 8;

const maxSize = minSize * 5;

@Component(

selector: 'my-sizer',

template: '''

<div>

<button (click)="dec()" [disabled]="size <= minSize">-</button>

<button (click)="inc()" [disabled]="size >= maxSize">+</button>

<label [style.font-size.px]="size">FontSize: {{size}}px</label>

</div>''',

exports: [minSize, maxSize],

)

class SizerComponent {

int _size = minSize * 2;

int get size => _size;

@Input()

void set size(/*String|int*/ val) {

int z = val is int ? val : int.tryParse(val);

if (z != null) _size = min(maxSize, max(minSize, z));

}

final _sizeChange = StreamController<int>();

@Output()

Stream<int> get sizeChange => _sizeChange.stream;

void dec() => resize(-1);

void inc() => resize(1);

void resize(int delta) {

size = size + delta;

_sizeChange.add(size);

}

}The initial size is an input value from a property binding.

Clicking the buttons increases or decreases the size, within min/max values constraints,

and then raises (emits) the sizeChange event with the adjusted size.

Here’s an example in which the AppComponent.fontSizePx is two-way bound to the SizerComponent:

<my-sizer [(size)]="fontSizePx" #mySizer></my-sizer>

<div [style.font-size.px]="mySizer.size">Resizable Text</div>The AppComponent.fontSizePx establishes the initial SizerComponent.size value.

Clicking the buttons updates the AppComponent.fontSizePx via the two-way binding.

The revised size value flows through to the style binding,

making the displayed text bigger or smaller.

The two-way binding syntax is really just syntactic sugar for a property binding and an event binding.

Angular desugars the SizerComponent binding into this:

<my-sizer [size]="fontSizePx" (sizeChange)="fontSizePx=$event"></my-sizer>The $event variable contains the payload of the SizerComponent.sizeChange event.

Angular assigns the $event value to the AppComponent.fontSizePx when the user clicks the buttons.

Clearly the two-way binding syntax is a great convenience compared to separate property and event bindings.

It would be convenient to use two-way binding with HTML form elements like <input> and <select>.

However, no native HTML element follows the x value and xChange event pattern.

Fortunately, the Angular NgModel directive is a bridge that enables two-way binding to form elements.

Built-in directives

Earlier versions of Angular included over seventy built-in directives. The community contributed many more, and countless private directives have been created for internal apps.

You don’t need many of those directives in Angular. You can often achieve the same results with the more capable and expressive Angular binding system. Why create a directive to handle a click when you can write a simple binding such as this?

<button (click)="onSave()">Save</button>You still benefit from directives that simplify complex tasks. Angular still ships with built-in directives; just not as many. You’ll write your own directives, just not as many.

This segment reviews some of the most frequently used built-in directives, classified as either attribute directives or structural directives.

Built-in attribute directives

Attribute directives listen to and modify the behavior of other HTML elements, attributes, properties, and components. They are usually applied to elements as if they were HTML attributes, hence the name.

Many details are covered in the Attribute Directives guide.

Many Angular packages such as the Router

and Forms packages define their own attribute directives.

This section is an introduction to the most commonly used attribute directives:

-

NgClass: Add and remove a set of CSS classes. -

NgStyle: Add and remove a set of HTML styles. -

NgModel: Two-way data binding to an HTML form element.

NgClass

You typically control how elements appear

by adding and removing CSS classes dynamically.

You can bind to the ngClass to add or remove several classes simultaneously.

A class binding is a good way to add or remove a single class.

<!-- toggle the "special" class on/off with a property -->

<div [class.special]="isSpecial">The class binding is special</div>To add or remove many CSS classes at the same time, the NgClass directive might be the better choice.

Try binding ngClass to a key:value control Map.

Each key of the object is a CSS class name; its value is true if the class should be added,

false if it should be removed.

Consider a setCurrentClasses component method that sets a component property,

currentClasses with an object that adds or removes three classes based on the

true/false state of three other component properties:

Map<String, bool> currentClasses = <String, bool>{};

void setCurrentClasses() {

currentClasses = <String, bool>{

'saveable': canSave,

'modified': !isUnchanged,

'special': isSpecial

};

}Adding an ngClass property binding to currentClasses sets the element’s classes accordingly:

<div [ngClass]="currentClasses">This div is initially saveable, unchanged, and special</div>It’s up to you to call setCurrentClasses(), both initially and when the dependent properties change.

NgStyle

You can set inline styles dynamically, based on the state of the component.

With NgStyle you can set many inline styles simultaneously.

A style binding is an easy way to set a single style value.

<div [style.font-size]="isSpecial ? 'x-large' : 'smaller'" >

This div is x-large or smaller.

</div>To set many inline styles at the same time, the NgStyle directive might be the better choice.

Try binding ngStyle to a key:value control Map.

Each key of the object is a style name; its value is whatever is appropriate for that style.

Consider a setCurrentStyles component method that sets a component property, currentStyles

with an object that defines three styles, based on the state of three other component propertes:

Map<String, String> currentStyles = <String, String>{};

void setCurrentStyles() {

currentStyles = <String, String>{

'font-style': canSave ? 'italic' : 'normal',

'font-weight': !isUnchanged ? 'bold' : 'normal',

'font-size': isSpecial ? '24px' : '12px'

};

}Adding an ngStyle property binding to currentStyles sets the element’s styles accordingly:

<div [ngStyle]="currentStyles">

This div is initially italic, normal weight, and extra large (24px).

</div>It’s up to you to call setCurrentStyles(), both initially and when the dependent properties change.

NgModel - Two-way binding to form elements with [(ngModel)]

When developing data entry forms, you often both display a data property and update that property when the user makes changes.

Two-way data binding with the NgModel directive makes that easy. Here’s an example:

<input [(ngModel)]="currentHero.name">Inside [(ngModel)]

Looking back at the name binding, note that

you could achieve the same result with separate bindings to

the <input> element’s value property and input event.

<input [value]="currentHero.name"

(input)="currentHero.name=$event.target.value" >That’s cumbersome. Who can remember which element property to set and which element event emits user changes? How do you extract the currently displayed text from the input box so you can update the data property? Who wants to look that up each time?

That ngModel directive hides these onerous details behind its own ngModel input and ngModelChange output properties.

<input

[ngModel]="currentHero.name"

(ngModelChange)="currentHero.name=$event">The ngModel data property sets the element’s value property and the ngModelChange event property

listens for changes to the element’s value.

The details are specific to each kind of element and therefore the NgModel directive only works for an element

supported by a ControlValueAccessor

that adapts an element to this protocol.

The <input> box is one of those elements.

Angular provides value accessors for all of the basic HTML form elements and the

Forms guide shows how to bind to them.

You can’t apply [(ngModel)] to a non-form native element or a third-party custom component

until you write a suitable value accessor,

a technique that is beyond the scope of this guide.

You don’t need a value accessor for an Angular component that you write because you

can name the value and event properties

to suit Angular’s basic two-way binding syntax and skip NgModel altogether.

The sizer shown above is an example of this technique.

Separate ngModel bindings is an improvement over binding to the element’s native properties. You can do better.

You shouldn’t have to mention the data property twice. Angular should be able to capture

the component’s data property and set it

with a single declaration, which it can with the [(ngModel)] syntax:

<input [(ngModel)]="currentHero.name">Is [(ngModel)] all you need? Is there ever a reason to fall back to its expanded form?

The [(ngModel)] syntax can only set a data-bound property.

If you need to do something more or something different, you can write the expanded form.

The following contrived example forces the input value to uppercase:

<input

[ngModel]="currentHero.name"

(ngModelChange)="setUppercaseName($event)">Here are all variations in action, including the uppercase version:

Built-in structural directives

Structural directives are responsible for HTML layout. They shape or reshape the DOM’s structure, typically by adding, removing, and manipulating the host elements to which they are attached.

The deep details of structural directives are covered in the Structural Directives guide, where you’ll learn the following:

- Why you must prefix the directive name with an asterisk (*).

- How to group elements when there is no suitable host element for the directive.

- How to write your own structural directive.

- Why you can apply only one structural directive to an element.

This section is an introduction to the common structural directives:

-

NgIf: Conditionally add or remove an element from the DOM. -

NgFor: Repeat a template for each item in a list. -

NgSwitch: Show only one of multiple possible elements.

NgIf

You can add or remove an element from the DOM by applying an NgIf directive to

that element (called the host elment).

Bind the directive to a condition expression like isActive in this example.

<my-hero *ngIf="isActive"></my-hero>Don’t forget the asterisk (*) in front of ngIf.

When the isActive expression returns a true value, NgIf adds the HeroComponent to the DOM.

When the expression is false, NgIf removes the HeroComponent

from the DOM, destroying that component and all of its sub-components.

Show/hide is not the same thing

You can control the visibility of an element with a class or style binding:

<!-- isSpecial is true -->

<div [class.hidden]="!isSpecial">Show with class</div>

<div [class.hidden]="isSpecial">Hide with class</div>

<!-- HeroDetail is in the DOM but hidden -->

<my-hero [class.hidden]="isSpecial"></my-hero>

<div [style.display]="isSpecial ? 'block' : 'none'">Show with style</div>

<div [style.display]="isSpecial ? 'none' : 'block'">Hide with style</div>Hiding an element is quite different from removing an element with NgIf.

When you hide an element, that element and all of its descendents remain in the DOM. All components for those elements stay in memory, and Angular might continue to check for changes. Your app might hold onto considerable computing resources, degrading performance for something the user can’t see.

When NgIf is false, Angular removes the element and its descendents from the DOM.

It destroys their components, potentially freeing up substantial resources,

resulting in a more responsive user experience.

The show/hide technique is fine for a few elements with few children.

Be wary of hiding large component trees; NgIf might be the safer choice.

Guard against null

The ngIf directive is often used to guard against null.

Show/hide is useless as a guard.

Angular will throw an error if a nested expression tries to access a property of null.

Here we see NgIf guarding two <div>s.

The currentHero name appears only when there is a currentHero.

The nullHero is never displayed.

<div *ngIf="currentHero != null">Hello, {{currentHero.name}}</div>

<div *ngIf="nullHero != null">Hello, {{nullHero.name}}</div>See also the safe navigation operator described below.

NgFor

NgFor is a repeater directive — a way to present a list of items.

You define a block of HTML that defines how a single item should be displayed.

You tell Angular to use that block as a template for rendering each item in the list.

Here is an example of NgFor applied to a simple <div>:

<div *ngFor="let hero of heroes">{{hero.name}}</div>You can also apply an NgFor to a component element, as in this example:

<my-hero *ngFor="let hero of heroes" [hero]="hero"></my-hero>Don’t forget the asterisk (*) in front of ngFor.

The text assigned to *ngFor is the instruction that guides the repeater process.

*ngFor microsyntax

The string assigned to *ngFor is not a template expression.

It’s a microsyntax — a little language of its own that Angular interprets.

The string "let hero of heroes" means:

Take each hero in the

heroeslist, store it in the localherolooping variable, and make it available to the templated HTML for each iteration.

Angular translates this instruction into a <template> around the host element,

then uses this template repeatedly to create a new set of elements and bindings for each hero

in the list.

Learn about the microsyntax in the Structural Directives guide.

Template input variables

The let keyword before hero creates a template input variable called hero.

The ngFor directive iterates over the heroes list returned by the parent component’s heroes property

and sets hero to the current item from the list during each iteration.

To access the hero’s properties,

reference the hero input variable within the ngFor host element

(or within its descendents).

Here hero is referenced first in an interpolation

and then passed in a binding to the hero property of the <my-hero> component.

<div *ngFor="let hero of heroes">{{hero.name}}</div>

<my-hero *ngFor="let hero of heroes" [hero]="hero"></my-hero>Learn more about template input variables in the Structural Directives guide.

*ngFor with index

The index property of the NgFor directive context returns the zero-based index of the item in each iteration.

You can capture the index in a template input variable and use it in the template.

The next example captures the index in a variable named i and displays it with the hero name like this.

<div *ngFor="let hero of heroes; let i=index">{{i + 1}} - {{hero.name}}</div>Learn about the other NgFor context values such as last, even,

and odd in the NgFor API reference.

*ngFor with trackBy

The NgFor directive can perform poorly, especially with large lists.

A small change to one item, an item removed, or an item added can trigger a cascade of DOM manipulations.

For example, re-querying the server might reset the list with all new hero objects.

Most, if not all, are previously displayed heroes.

You know this because the id of each hero hasn’t changed.

But Angular sees only a fresh list of new object references.

It has no choice but to tear down the old DOM elements and insert all new DOM elements.

Angular can avoid this churn with trackBy.

Add a method to the component that returns the value NgFor should track.

In this case, that value is the hero’s id.

Object trackByHeroId(_, dynamic o) => o is Hero ? o.id : o;In the microsyntax expression, set trackBy to this method.

<div *ngFor="let hero of heroes; trackBy: trackByHeroId">

({{hero.id}}) {{hero.name}}

</div>Here is an illustration of the trackBy effect.

“Reset heroes” creates new heroes with the same hero.ids.

“Change ids” creates new heroes with new hero.ids.

- With no

trackBy, both buttons trigger complete DOM element replacement. - With

trackBy, only changing theidtriggers element replacement.

The NgSwitch directives

NgSwitch is like the Dart switch statement.

It can display one element from among several possible elements, based on a switch condition.

Angular puts only the selected element into the DOM.

NgSwitch is actually a set of three, cooperating directives:

NgSwitch, NgSwitchCase, and NgSwitchDefault as seen in this example.

<div [ngSwitch]="currentHero.emotion">

<happy-hero *ngSwitchCase="'happy'" [hero]="currentHero"></happy-hero>

<sad-hero *ngSwitchCase="'sad'" [hero]="currentHero"></sad-hero>

<confused-hero *ngSwitchCase="'confused'" [hero]="currentHero"></confused-hero>

<unknown-hero *ngSwitchDefault [hero]="currentHero"></unknown-hero>

</div>You might come across an NgSwitchWhen directive in older code.

That is the deprecated name for NgSwitchCase.

NgSwitch is the controller directive. Bind it to an expression that returns the switch value.

The emotion value in this example is a string, but the switch value can be of any type.

Bind to [ngSwitch]. You’ll get an error if you try to set *ngSwitch because

NgSwitch is an attribute directive, not a structural directive.

It changes the behavior of its companion directives.

It doesn’t touch the DOM directly.

Bind to *ngSwitchCase and *ngSwitchDefault.

The NgSwitchCase and NgSwitchDefault directives are structural directives

because they add or remove elements from the DOM.

-

NgSwitchCaseadds its element to the DOM when its bound value equals the switch value. -

NgSwitchDefaultadds its element to the DOM when there is no selectedNgSwitchCase.

The switch directives are particularly useful for adding and removing component elements.

This example switches among four “emotional hero” components defined in the hero_switch_components.dart file.

Each component has a hero input property

which is bound to the currentHero of the parent component.

Switch directives work as well with native elements and web components too.

For example, you can replace the <confused-hero> switch case with the following.

<div *ngSwitchCase="'confused'">Are you as confused as {{currentHero.name}}?</div>Template reference variables ( #var )

A template reference variable is often a reference to a DOM element within a template. It can also refer to an Angular component or directive or a web component.

Use the hash symbol (#) to declare a reference variable.

The #phone declares a phone variable on an <input> element.

<input #phone placeholder="phone number">You can refer to a template reference variable almost anywhere in the template

(see notes below for exceptions).

The phone variable declared on this <input> is consumed in a <button> on

the other side of the template

<input #phone placeholder="phone number">

<!-- lots of other elements -->

<!-- phone refers to the input element; pass its `value` to an event handler -->

<button (click)="callPhone(phone.value)">Call</button>How a reference variable gets its value

In most cases, Angular sets the reference variable’s value to the element on which it was declared.

In the previous example, phone refers to the phone number <input> box.

The phone button click handler passes the input value to the component’s callPhone method.

But a directive can change that behavior and set the value to something else, such as itself.

The NgForm directive does that.

The following is a simplified version of the form example in the Forms guide.

<form (ngSubmit)="onSubmit(heroForm)" #heroForm="ngForm">

<div class="form-group">

<label for="name">Name

<input class="form-control"

ngControl="name"

required

[(ngModel)]="hero.name">

</label>

</div>

<button type="submit" [disabled]="!heroForm.form.valid">Submit</button>

</form>

<div [hidden]="!heroForm.form.valid">

{{submitMessage}}

</div>A template reference variable, heroForm, appears three times in this example, separated

by a large amount of HTML.

What is the value of heroForm?

The heroForm is a reference to an Angular

NgForm

directive with the ability to track the value and validity of every control in the form.

The native <form> element doesn’t have a form property.

But the NgForm directive does, which explains how you can disable the submit button

if the heroForm.form.valid is invalid and pass the entire form control tree

to the parent component’s onSubmit method.

Template reference variable warning notes

A template reference variable (#phone) is not the same as a template input variable (let phone)

such as you might see in an *ngFor.

Learn the difference in the Structural Directives guide.

The scope of a reference variable is the entire template, unless it’s declared within an embedded view controlled by a structural directive. Reference variables declared within an embedded view are only visible to the portion of the template embedded by the structural directive. Note that a reference variable declared outside an embedded view can be referenced from within it, but not the other way around.

Do not define the same variable name more than once in the same template. The runtime value will be unpredictable.

Input and output properties ( @Input and @Output )

So far, this page has focused mainly on binding to component members within template expressions and statements that appear on the right side of the binding declaration. A member in that position is a data binding source.

This section concentrates on binding to targets, which are directive properties on the left side of the binding declaration. These directive properties must be declared as inputs or outputs.

Remember: All components are directives.

Note the important distinction between a data binding target and a data binding source.

The target of a binding is to the left of the =.

The source is on the right of the =.

The target of a binding is the property or event inside the binding punctuation: [], () or [()].

The source is either inside quotes (" ") or within an interpolation ({{}}).

Every member of a source directive is automatically available for binding. You don’t have to do anything special to access a directive member in a template expression or statement.

You have limited access to members of a target directive. You can only bind to properties that are explicitly identified as inputs and outputs.

In the following snippet, iconUrl and onSave are data-bound members of the AppComponent

and are referenced within quoted syntax to the right of the equals (=).

<img [src]="iconUrl"/>

<button (click)="onSave()">Save</button>They are neither inputs nor outputs of the component. They are sources for their bindings.

The targets are the native <img> and <button> elements.

Now look at a another snippet in which the HeroComponent

is the target of a binding on the left of the equals (=).

<my-hero [hero]="currentHero" (deleteRequest)="deleteHero($event)">

</my-hero>Both HeroComponent.hero and HeroComponent.deleteRequest are on the left side of binding declarations.

HeroComponent.hero is inside brackets; it is the target of a property binding.

HeroComponent.deleteRequest is inside parentheses; it is the target of an event binding.

Declaring input and output properties

Target properties must be explicitly marked as inputs or outputs.

In the HeroComponent, such properties are marked as input or output properties using annotations.

@Input()

Hero hero;

final _deleteRequest = StreamController<Hero>();

@Output()

Stream<Hero> get deleteRequest => _deleteRequest.stream;Input or output?

Input properties usually receive data values. Output properties expose event producers, such as Stream objects.

The terms input and output reflect the perspective of the target directive.

HeroComponent.hero is an input property from the perspective of HeroComponent

because data flows into that property from a template binding expression.

HeroComponent.deleteRequest is an output property from the perspective of HeroComponent

because events stream out of that property and toward the handler in a template binding statement.

Aliasing input/output properties

Sometimes the public name of an input/output property should be different from the internal name.

This is frequently the case with attribute directives.

Directive consumers expect to bind to the name of the directive.

For example, when you apply a directive with a myClick selector to a <div> tag,

you expect to bind to an event property that is also called myClick.

<div (myClick)="clickMessage=$event" clickable>click with myClick</div>However, the directive name is often a poor choice for the name of a property within the directive class.

The directive name rarely describes what the property does.

The myClick directive name is not a good name for a property that emits click messages.

Fortunately, you can create a public name for the property that meets conventional expectations,

while using a different name internally.

In the example immediately above, the code binds through the myClick alias to

the directive’s own clicks property.

To specify the alias for the property name, pass the alias into the input/output decorator like this:

final _onClick = StreamController<String>();

// @Output(alias) propertyName = ...

@Output('myClick')

Stream<String> get clicks => _onClick.stream;Template expression operators

The template expression language employs a subset of Dart syntax supplemented with a few special operators for specific scenarios. The next sections cover two of these operators: pipe and safe navigation operator.

The pipe operator ( | )

The result of an expression might require some transformation before it’s ready to use in a binding. For example, you might display a number as a currency, force text to uppercase, or filter a list and sort it.

Angular pipes are a good choice for small transformations such as these.

Pipes are simple functions that accept an input value and return a transformed value.

They’re easy to apply within template expressions, using the pipe operator (|):

<div>Title through uppercase pipe: {{title | uppercase}}</div>The pipe operator passes the result of an expression on the left to a pipe function on the right.

You can chain expressions through multiple pipes:

<!-- Pipe chaining: convert title to uppercase, then to lowercase -->

<div>

Title through a pipe chain:

{{title | uppercase | lowercase}}

</div>You can also apply parameters to a pipe:

<!-- pipe with configuration argument => "February 25, 1970" -->

<div>Birthdate: {{currentHero?.birthdate | date:'longDate'}}</div>The json pipe can be helpful for debugging bindings:

<div>{{currentHero | json}}</div>The generated output looks something like this:

{ "id": 0, "name": "Hercules", "emotion": "happy",

"birthdate": "1970-02-25T08:00:00.000Z",

"url": "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065832/",

"rate": 325 }

The safe navigation operator ( ?. ) and null property paths

The Angular safe navigation operator (?.), like the Dart conditional member

access

operator, is a fluent and convenient way to

guard against null values in property paths.

Here it is, protecting against a view render failure if the currentHero is null.

The current hero's name is {{currentHero?.name}}What happens when the following data bound title property is null?

The title is {{title}}The view still renders but the displayed value is blank; you see only “The title is” with nothing after it. That is reasonable behavior. At least the app doesn’t crash.

Suppose the template expression involves a property path, as in this next example

that displays the name of a null hero.

The null hero's name is {{nullHero.name}}

Dart throws an exception, and so does Angular:

EXCEPTION: The null object does not have a getter 'name'.

Worse, the entire view disappears.

This would be reasonable behavior if the hero property could never be null.

If it must never be null and yet it is null,

that’s a programming error that should be caught and fixed.

Throwing an exception is the right thing to do.

On the other hand, null values in the property path might be OK from time to time, especially when the data are null now and will arrive eventually.

While waiting for data, the view should render without complaint, and

the null property path should display as blank just as the title property does.

Unfortunately, the app crashes when the currentHero is null.

You could code around that problem with *ngIf.

<!--No hero, div not displayed, no error -->

<div *ngIf="nullHero != null">The null hero's name is {{nullHero.name}}</div>These approaches have merit but can be cumbersome, especially if the property path is long.

Imagine guarding against a null somewhere in a long property path such as a.b.c.d.

The Angular safe navigation operator (?.) is a more fluent and convenient way to guard against nulls in property paths.

The expression bails out when it hits the first null value.

The display is blank, but the app keeps rolling without errors.

<!-- No hero, no problem! -->

The null hero's name is {{nullHero?.name}}It works perfectly with long property paths such as a?.b?.c?.d.

Summary

You’ve completed this survey of template syntax. Now it’s time to put that knowledge to work on your own components and directives.